Dr. Lisa Funnell

Award-Winning Author | Media Educator & Consultant | “Dr 007” | Director of Communications, G-Woman Media

By Dr. Lisa Funnell

For decades, disability activism has existed at the margins of broader social justice movements. Even within institutions, accessibility is frequently siloed — treated as an add-on rather than a core pillar of equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) initiatives. This separation has shaped not only our social and political landscapes, but also our cultural ones. Nowhere is this more visible than in popular film.

Blockbuster cinema plays a powerful role in shaping how we understand identity, power, and “normalcy.” And while many viewers dismiss franchises like James Bond as “just entertainment,” the messages embedded within them especially around disability are far from harmless. In fact, they frequently reinforce ableist tropes that have circulated for over a century.

One of the most persistent of these tropes is the use of facial scarring and other visible differences to signify villainy. As the Craig era Bond films (2006-21) demonstrate, this practice is not only alive and well, but accelerating at a moment when disability advocates are calling loudly for change.

Why Disability Representation in Film Falls Short

When disability appears on screen, it is almost always shaped—and played—by people without disabilities. As scholar Elisa Shaholli notes, this gives nondisabled creators the power to define the role; while disability may be visible in the frame it is erased from the production process.

This absence of lived experience contributes to harmful patterns:

- Disabilities presented as symbols rather than realities

- Characters defined by their impairments rather than their identities

- Facial differences coded as evidence of moral corruption

These tropes are not new. As early as the silent film era, villains were marked by scars, burns, alopecia, albinism, and other dermatologic features meant to evoke unease and “otherness.” As Paul Longmore argues, such depictions position disabled characters as less human and, at times, literally monstrous.

These old ideas continue to shape contemporary storytelling. And franchises with global reach, like James Bond, carry particular weight in reinforcing them.

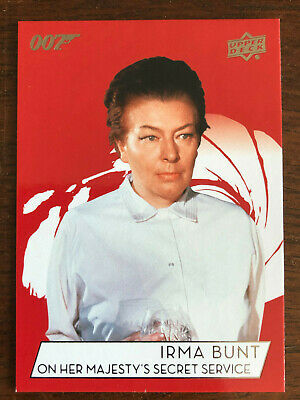

Bond’s History of Villainizing Facial Difference

The Bond franchise has always relied on physical contrast to build its hero. Bond’s masculinity is elevated by juxtaposing his “ideal” body against that of adversaries who are framed as freakish, excessive, or impaired.

Before the 1990s, facial scarring was rare in Bond films. Blofeld’s scar in You Only Live Twice (1967) is the standout example. But with the Brosnan era—and even more so with the Craig era—facial difference becomes a core shorthand for villainy.

Across the Craig films, this trope is used repeatedly:

This is not incidental. These creative choices signal a deeper problem: Ableism has become embedded in the visual language of the Bond brand.

When Tradition Becomes a Problem

Some defenders of the franchise argue that scars are simply an homage to Bond history. Others claim that visible differences efficiently communicate a backstory in a film with limited time.

But these justifications ignore three critical realities:

1. Audiences are harmed by this shorthand.

Campaigns like #IAmNotYourVillain—supported by UK charity Changing Faces—document how cinematic scar tropes fuel real-world discrimination.

2. Industry leaders have already acknowledged the problem.

In 2018, the British Film Institute (BFI) committed to no longer funding films that use facial difference as visual shorthand for villainy.

3. Bond has continued anyway.

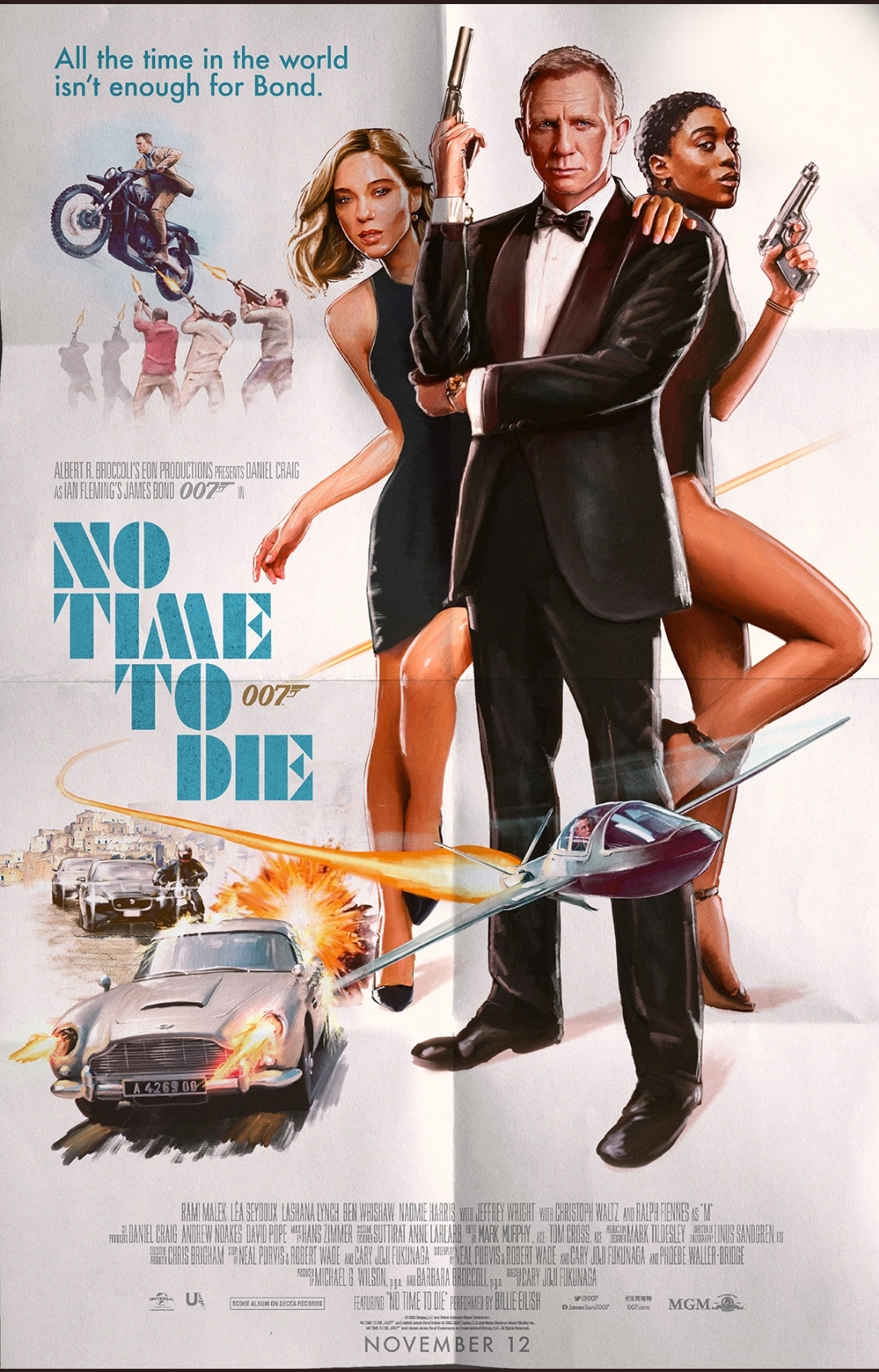

Despite global conversations about disability representation, No Time To Die (2021) features three villains with facial scarring—its highest count yet.

At that point, it is no longer coincidence. It is a pattern.

Why This Matters for Bond’s Future

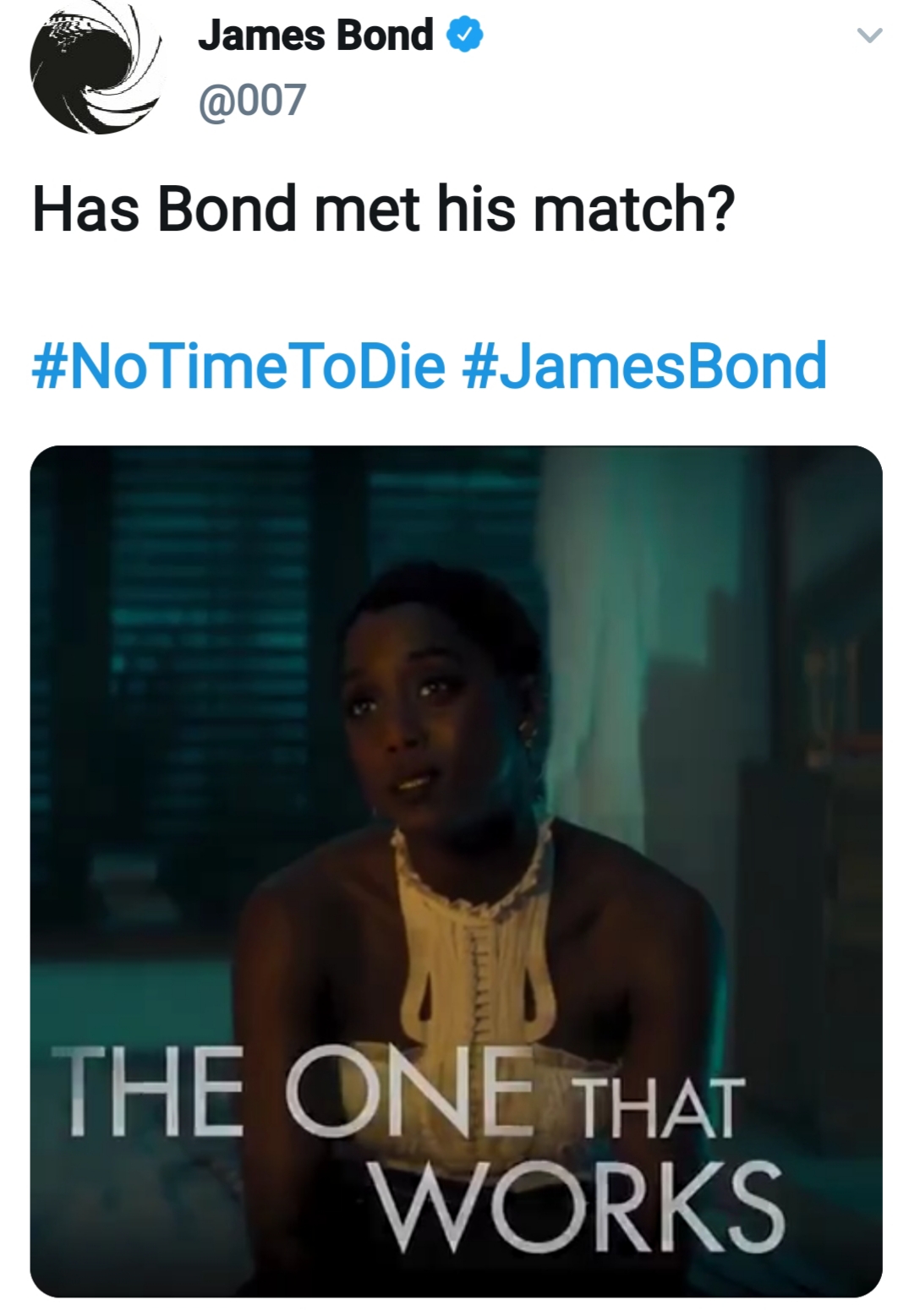

The Craig era is often celebrated for its “progress” including the casting of Black actors as Felix Leiter and Moneypenny, or the brief re-assignment of the 007 number to Lashana Lynch.

But representation gains in gender and race cannot be used to offset ableist practices. A franchise cannot be progressive only when easy and where convenient.

What’s more, these creative decisions reflect the values of the core team shaping Bond storytelling for over two decades—producers Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson, long-time screenwriters Neal Purvis and Robert Wade, and directors including Sam Mendes.

The Bond Franchise Has a Choice to Make

As Bond enters another transition—with a new lead and a new creative vision—the question is not simply who the next 007 will be. The deeper question is:

Will the franchise continue relying on outdated, ableist narrative devices?

Or will it evolve alongside the audiences who have been calling for change?

Bond has survived for over 60 years because it adapts to shifting cultural landscapes. But progression requires more than casting choices or gender-politics updates. It requires rethinking how stories are told and who gets harmed in the storytelling process.

The old Bond is dead. It’s time for the old representational practices to die with him.

If the next era of Bond wants to remain relevant, compelling, and socially conscious, then the franchise must finally retire the trope of scarring-as-villainy and embrace a world where disability representation is neither monstrous nor metaphorical, but fully human.

Co-written with Klaus Dodds

Water is a critical resource to the sustainment of human, plant, and animal life. While water is plentiful on earth, only 3 percent of it is freshwater and more than half is inaccessible as it is frozen in glaciers. Moreover, freshwater is not equally distributed on earth and six countries account for more than half of the world’s fresh water supply: Brazil, Russia, Canada, Indonesia, China, and Columbia (Krapivin and Varotsos, 2008, p.495).

Water Wars and Bond Villainy in Quantum of Solace

Although water is a renewable resource, the world’s supply of fresh water is steadily decreasing due to contamination and overuse (via industrialization and agriculture), and nearly a billion people worldwide lack access to safe drinking water. As a result, water has increasingly become a source of conflict as nations, regions, and groups fight to control water resources. And it is the conflict over water, and not oil, that is at the heart of Quantum of Solace.

Bolivia is not only the setting for the film but it also provides the best historical example of the fight over water privatization. In 1999, the World Bank recommended the privatization of the municipal water supply in Cochabamba and El Alto/La Paz, Bolivia’s two largest cities. As noted by Jim Shultz “the World Bank argued that handing water over to foreign corporations was essential in order to open the door to needed investment and skilled management” (2008, p.126). In Cochabamba, this led to a four-year contract with an American consortium, Bechtel Corporation of California, who doubled the price of water upon taking it over, leaving many poor families with the choice between buying water or food. This increase led to citywide protests and eventually the government revoked its water privatization legislation, after first attempting to protect the agreement by instituting martial law (McPhail and Walters, 2009, p.171). A similar uprising in 2005 led to the Bolivian government’s cancellation of a water privatization deal in El Alto/La Paz with the Suez Corporation of France (Shultz, 2008, p.126).

Water privatization in Bolivia is the central objective for the villain, Dominic Greene, in Quantum of Solace. Greene masquerades as an environmentalist and philanthropist who espouses water and environmental conservation. He is the founder of Greene Planet, an environmental corporation that buys up large portions of land for ecological preservation. During a fundraiser in Bolivia, he describes his Tierra Project as “one small part of a global network of eco-parks that Greene Planet has created to rejuvenate the world on the verge of collapse.” This project, however, is really a Quantum initiative designed to covertly establish water privatization in Bolivia.

When Greene describes the processes by which deforestation in Bolivia has led to desertification and an increase in the price of water, he is referring to the actions that he has set in motion through his multinational corporations. What he does not mention is the way in which he collected and stored the freshwater underground by erecting dams that have stopped the resource from flowing to the rest of the country. Through the vilification of Greene and his corporation, the film strongly criticizes water privatization and the foreign acquisition of domestic freshwater reserves (while appearing more ambivalent on oil rights). Moreover, the film positions Quantum, an international terrorist organization, in the role of the World Bank and condemns their capital programs in developing nations like Bolivia. Importantly, it is Bond as an agent of Britain who restores geopolitical order and returns oversight of local resources back to the Bolivian government.

Bond, Water, and Gender in the 007 Franchise

In Quantum of Solace, water conflict takes on gendered connotations. Water has long played a critical role in the Bond films. Bond is frequently immersed in water: he fights in and under water, travels on and under water, and sometimes has to prevent water from overwhelming places (e.g. A View to a Kill). He understands the role that water pressure can play on the immersed body (e.g. For Your Eyes Only) and is adept at adjusting his behavior to take constraints and opportunities offered by water such as impromptu water-skiing (e.g. License to Kill).

Although Bond frequently operates in water, the element has historically been associated with women due to the reproductive capacity of the female body and its link to the ‘waters of life;’ in various art and written texts, the female body is described as a vessel/container and women have largely been essentialized in relation to their wombs in both society and culture. This association is forwarded in the Bond films in many of the opening credit sequences, which feature women underwater moving around (and seducing) men. According to Eileen Rositzka, these women “conjure up images of the nymphs from Greek or Latin mythology—beautiful maidens filling nature with life. A nymph is also regarded as a siren who lures a man—to his death” (2015, p.153). As such, these anonymous women are presented as being threatening to Bond as they distract him from his mission.

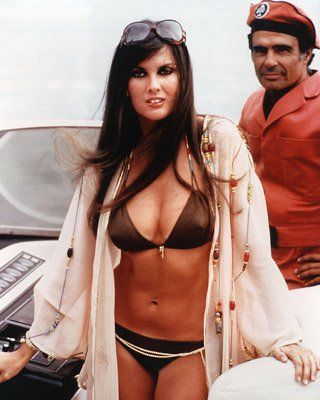

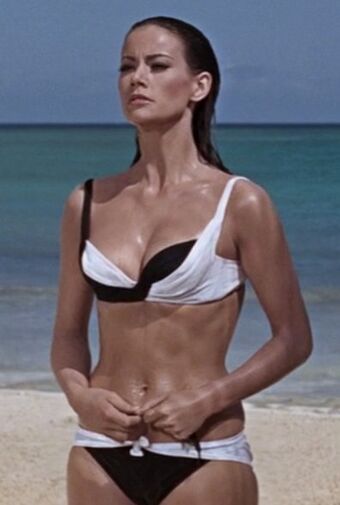

The Bond Girls in the film proper are also strongly associated with water and depicted as water nymphs and sirens. This connection was established in the inaugural Dr. No, which features Honey Ryder emerging from the sea while singing (Piotrowska, 2015, p.171). The combination her image and voice are so appealing that they attract the male gaze of Bond and his helper Quarrel who stop and stare thereby haling narrative progress in order to look at her. Moreover, it is Ryder’s knowledge of the island and its waterways that facilitates their escape from capture. Ryder is the first in a series of Bond Girls that Bond first sees (e.g. Jinx Johnson), meets (e.g. Domino Derval), kisses (e.g. Wai Lin), and works with (e.g. Melina Havelock) underwater in the series. The film enrolls patriarchal sentiments by associating women with the feminine element of water and Bond’s subsequent use and mastery over them (both separately and combined).

Water in the Daniel Craig Era

As revisionist films, the orphan origin trilogy recalibrates many elements characteristic of the series including the association of water with women. In Casino Royale, it is Bond and not his lover Vesper Lynd who is envisaged through Bond Girl iconography. On two occasions, Bond emerges from the sea in a bathing suit and his body is positioned as the object of the gaze for two female onlookers: Solange watches Bond swim along the coastline while Lynd waits for him to exit the ocean on the beach (Funnell, 2011a, p.467). Through the intertextual referencing of Honey Ryder, Bond is depicted through the well-known iconography of the Bond Girl: he is positioned as the object of the gaze and associated with water.

This connection is carried into the climax of the film in which Bond is unable to save a drowning Lynd from a building that has collapsed into the Venice canal; by locking herself in the elevator carriage, Lynd commits suicide by drowning and it is Bond who lives and carries on. This effectively works to dissociate women with water while masculinizing the element. This relationship is carried over into the next film, Quantum of Solace, as the first three Craig era films are more serial in nature and constitute a trilogy (with Spectre possibly being the starting point of a ‘Blofeld trilogy’) that conveys the orphan origin story of Bond, which is concluded in Skyfall.

In Quantum of Solace, Bond’s association with water is both literal and symbolic. On the one hand, Bond uses his instincts and skill set to discover the man-made aquifer underground and deduce Greene’s master plan. After Bond explains the situation to Camille Montes, shots of the pair walking through the mine shaft and then through the desert are intercut with images of the local villagers congregating around a small water tower that is empty and discussing the situation. Interestingly, the majority of villagers are men even though in most developing countries where water is collected outside the home it is women and girls who carry out the task. The foregrounding of men in this scene emphasizes the threat of water shortage on the community (rather than individual households) and in most patriarchal societies it is men who engage in social dialogue about local issues.

However, the scene does not contain subtitles and most audiences will not be able to discern the concerns relayed through this exchange. As a result, these voices are rendered less important like background noise—a symbolic representation of their limited power and lack of involvement in water privatization—as they cannot be accessed and understood. And it is Montes, a rogue Bolivian agent, who stands in and speaks out for the Bolivian people (and not the Bolivian government).

The relationship that develops between Bond and Montes can be read in both geopolitical and elemental terms. On the one hand, Bond as an agent of Britain intervenes in the Bolivian water conflict through his collaboration with Montes, and their growing friendship stands in for the strengthening of British and Bolivian relations. Although the government of Bolivia is in flux, Bond supports the people who are represented by Montes in the film.

On the other hand, Bond and Montes are associated with the antithetic elements of water and fire respectively (see above), and their collaboration is necessary to relieving the drought in Bolivia. After Montes kills Medrano in the climax of the film, the eco hotel becomes engulfed in fire and she requires rescue from Bond who makes his way through the inferno untouched by the flames and carries her to safety. As a result, Bond is metaphorically associated with “the waters of life” as he saves Montes from the fiery danger inflicted by Medrano and Bolivia from the water collection and privatization of Greene.

Bond’s association with water continues into the denouement when he travels to Russia to confront Lynd’s former lover, Yusef Kabira, a Quantum operative who seduces women working in intelligence agencies in order to gain access to government information. After Bond interrogates the man, he leaves the apartment complex and indicates to M that he has received closure as he throws Lynd’s necklace to the ground. The film relies on pathetic fallacy to externalize the emotions of the stoic Bond through the falling snow.

On the one hand, the snow—water in liquid form—signals that Bond’s thirst for vengeance has been quenched as he has found the man responsible for the manipulation of Lynd. The scene can be read as Bond finally letting go of his anger and this closure takes the form of snow falling around him. On the other hand, the snow represents the freezing or hardening of Bond’s heart, a necessary step to ensuring his physical and emotional safety as a secret agent. In literal and symbolic ways, Bond resolves the conflict associated with water in both the geopolitical and personal realm.

As a character, James Bond is not only defined by his actions (i.e. what he does), but also by his social privilege (i.e. who he is) as relayed through his encounters with other characters and especially women. The heroic identity of Bond is rooted in the British lover literary tradition (Hawkins 29-30) which relies on the ‘lover’ stereotype of masculinity and is conveyed through virility. As a result, seducing and sexually satisfying (heroic and villainous) women is built into the world of Bond and this heteronormative performativity is framed as a tipping point that ensures mission success (Black 107). Since the inaugural Dr. No (Young 1962), the cinematic world of Bond has strongly relied on a network of women to shape the heroic image and iconic identity of Bond.

While the women featured in the Bond series range in terms of their role (from primary characters to secondary figures), affiliation (heroic and villainous), and social locations (such as race, sexual orientation, and age), they are often grouped together under the umbrella term ‘Bond Girl.’ This academic and popular moniker not only obscures the diversity of female representation but also reduces the narrative importance of women by presenting them as functions of Bond (i.e. they are Bond’s girl).

Moreover, the use of the term ‘girl’ to describe women infantilizes them and diminishes their professional accomplishments while stressing their sexual availability to Bond (with womanhood being reserved in the series for marriage and motherhood). By comparison, the men featured in Bond films are given standalone identities (i.e. they are not Bond’s men) and are never insulted/infantilized through their referencing as ‘Bond Boys.’ While it is difficult to avoid using the term ‘Bond Girl’ due to its cultural pervasiveness, it is important to be attentive to the messages being relayed through it about gender, power, and identity in series (Funnell, “Reworking” 12).

Bond interacts with a variety of women in each film. The first major category consists of female protagonists who are envisaged through the Bond Girl archetype. Here the term Bond Girl is reserved for one woman in each film who is the primary hero and is romantically involved with Bond in the end (Funnell, “From” 63). She is frequently depicted as an object of desire via ‘the male gaze’ (see Mulvey 1988) as Bond and the villain compete for her affections.

The Bond Girl has gone through various phases including English Partner (1962-1969), American Sidekick (1971-1989), and Action Hero (1995-2002), with the archetype being deconstructed and reintroduced across the Craig Era (2006-2015; see Funnell, ‘Reworking’ 2018). While Bond Girls vary in terms of their narrative importance, autonomy in decision making, heroic competency, and core abilities (in such areas of fighting, driving, and intelligence gathering, among others), their social locations remain relatively consistent. For instance, a white woman has been featured as the lead protagonist in twenty-one of twenty-four (88%) Bond films. This draws attention to the centrality of whiteness in the casting for this coveted role across five decades.

The second major category consists of villainous women who often work as henchpeople for the arch-villain. Much like the Bond Girl, female villains shift through various phases of representation with their frequency of appearance, narrative importance, autonomy, and competency fluctuating in response to changing waves of feminism: second wave (1960s), antifeminist backlash (1970s), third wave (1980s), and postfeminist (1990s onwards) movements (see Funnell ‘Negotiating’ 2011).

Female villains frequently challenge the heteropatriarchy and especially their presumed/prescribed position both sexually and socially below Bond. They are killed off in their films in order to resolve the threat to Bond’s libidinal masculinity and restore phallocentric order. While there is greater racial diversity amongst female villains than Bond Girls, the series relies on problematic stereotypes when representing women of color. Travis Wagner notes that black women in particular have been presented in deeply troubling ways through hypersexualization and treated as disposable objects of pleasure in the series (see Wagner 2015).

The third category consists of recurring female characters within MI6 who engage with Bond largely in professional contexts. Miss/Eve Moneypenny is the most recurring female figure in the series and works as the personal assistant to Bond’s boss, M. She has long served as a trusted friend and ally to Bond, and her flirtatious exchanges with Bond never progress romantically outside of the office. Lois Maxwell pioneered the role but was replaced after A View to a Kill (Glen 1985) when she was deemed too old to play the part.

By comparison, Desmond Llewelyn, who was first featured in From Russia with Love (Young 1963) was able to continue playing the role of Q until his death in 1999. Their differing career trajectories draw attention the intersection of gender and age in the series (Dodds 215); the series relies strongly on the aesthetic ideal of femininity (which is largely white, slim, and young) in the depiction of female characters and relays the impression that women working with/under Bond are to serve as objects of desire for him and the (presumed male target) viewer by extension.

In Skyfall (Mendes 2012), Moneypenny was given an origin story and introduced as a field agent who was subsequently demoted to a desk job after accidentally shooting Bond in the field. Unlike Bond, Moneypenny has yet to be given a redemption narrative after making one mistake in the field and this double standard can be attributed, at least in part, to her being a black woman (played by Naomie Harris) in the Craig era films (see Kristin Shaw 2015).

Age, professional experience, and race also play a role in shaping the identity of Judi Dench who plays Bond’s boss M across the Brosnan (1995-2002) and Craig era films (2006-2015). While Dench’s M is clearly distinguished from her male predecessors via gender, the films also stress her lack of military/field experience and imply that she rose through the ranks via civil service. She is referred to as a ‘bean counter’ and the ‘evil queen of numbers’ by her agents and staff who open question her authority (see Patton 2015, Holliday 2015). The early films also mention that she is married with children.

While Dench’s M is shown to navigate the sexual politics of military and government agencies, she remains privileged by her race and her confrontation of sexism does not explicitly address the racism within the organization. This is most evident in Skyfall when she sides with and supports Bond, who is not physically fit to return to the field, over Moneypenny who followed her order to take the unclean shot at Bond; Bond is supported by M while Moneypenny is disciplined and demoted.As the series progresses, the films increasingly stress the maternal nature of Dench’s M (who is now widowed and estranged from her biological children) and by the end of Skyfall she requires the protection of Bond who is positioned as her (only family and) surrogate son.

Bond also interacts with a series of secondary women across his films who range in terms of their role, screen time, autonomy, and heroic competency as well as whether or not they are (important enough to be) named. Charles Burnetts likens these women to ‘fluffers’ in the porn industry who keep the male star aroused until his primary interest arrives at which time they disappear off-screen (60).

Moreover, the opening credits feature the (semi-)nude bodies of women cast in shadow/silhouette dancing/moving in a variety of scenarios. According to Sabine Planka, ‘sex sells’ and the Bond franchise serves up the bodies of these nameless women who are not featured in the film proper as appetizers to stimulate the viewer’s appetite (141). These images are paired with title tracks that are predominantly performed by women or male singers with a ‘feminine quality’ to their voice (Piotrowska 167). Their melodies are often woven into the soundtrack and help to shape (and arguably provide balance to) the (masculine) world of Bond. While there is greater diversity amongst the musical performers (i.e. the disembodied voices) who are heard and not seen, the anonymous and often silent women featured on screen are more consistent in terms of their race (i.e. white), physique (i.e. slim), and age (i.e. young).

The Bond franchise has also historically relied on women in their extra-textual materials and marketing strategies. For instance, in the first four decades of the franchise, scantily clad women are featured on Bond movie posters in sexually suggestive poses as well as touching or looking at Bond in a longing way. These posters simultaneously convey and confirm the heroic masculinity of Bond who is presented as gentleman (via tuxedo) hero (via holding his gun) who is also desired by a bevy of beautiful women (i.e. the lover).

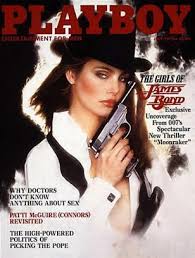

Playboy magazine was also frequently used to promote the franchise and since 1965 has (un)covered many of the Bond films with special issues like “007 Oriental Eyefuls” for You Only Live Twice (Gilbert 1967), “Vegas Comes Up 007” for Diamonds Are Forever (Hamilton 1971) and “Women of 007” published in conjunction with The Living Daylights (Glen 1987). These photo spreads not only help to confirm the male gaze and emphasize the pleasures of looking at the women of Bond (see Hines 2018), but they also offer the consumer a glimpse of what Bond gets to see behind closed doors as the film themselves do not feature nudity. The franchise has expanded beyond Playboy and utilizes other men’s magazines in its marketing of Bond women in various stages of undress.

Overall, the Bond franchise has historically relied on women and especially the aesthetic ideal of femininity to both shape and promote the world of Bond to a presumed male viewership.

For a detailed discussion, see my article with Tyler Johnson on “Properties of a Lady: Public Perceptions of Gender in the James Bond Franchise”

References

- Black, Jeremy. The Politics of James Bond: From Fleming’s Novels to the Big Screen. London: Praeger, 2001.

- Burnetts, Charles. “Bond’s Bit on the Side: Race, Exoticism and the Bond “Fluffer” Character.” For His Eyes Only: The Women of James Bond. Ed. Lisa Funnell. London, UK: Wallflower Press, 2015. 60-69.

- Dodds, Klaus. “‘It’s Not For Everyone’: James Bond and Miss Moneypenny in Skyfall.” For His Eyes Only: The Women of James Bond. Ed. Lisa Funnell. London, UK: Wallflower Press, 2015. 214-223.

- Funnell, Lisa. “From English Partner to American Action Hero: The Heroic identity and Transnational Appeal of the Bond Girl.” Heroes and Heroines: Embodiment, Symbolism, Narratives and Identity. Ed. Christopher Hart. Kingswinford, UK: Midrash, 2008. 61-80.

- Funnell, Lisa. “Negotiating Shifts in Feminism: The ‘Bad’ Girls of James Bond.” Women on Screen: Feminism and Femininity in Visual Culture. Ed. Melanie Waters. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2011. 199-212.

- Funnell, Lisa. “Reworking the Bond Girl Concept in the Daniel Craig Era.” Journal of Popular Film and Television 46.1 (2018): 11-21.

- Hawkins, Harriet. Classics and Trash: Traditions and Taboos in High Literature and Popular Modern Genres. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990.

- Hines, Claire. The Playboy and James Bond: 007, Ian Fleming, and Playboy Magazine. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2018.

- Holliday, Christopher. “Mothering the Bond-M Relation in Skyfall and the Bond Girl Intervention.” For His Eyes Only: The Women of James Bond. Ed. Lisa Funnell. London, UK: Wallflower Press, 2015. 265-273.

- Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Feminism and Film Theory. Ed. Constance Penley. New York: Routledge, 1988. 57-68.

- Patton, Brian. “M, 007, and the Challenge of Female Authority in the Bond Franchise.” For His Eyes Only: The Women of James Bond. Ed. Lisa Funnell. London, UK: Wallflower Press, 2015. 246-254.

- Planka, Sabine. “Female Bodies in the James Bond Title Sequences.” For His Eyes Only: The Women of James Bond. Ed. Lisa Funnell. London, UK: Wallflower Press, 2015. 139-147.

- Piotrowski, Anna G., “Female Voice and the Bond Films.” For His Eyes Only: The Women of James Bond. Ed. Lisa Funnell. London, UK: Wallflower Press, 2015. 167-175.

- Shaw, Kristin. “The Politics of Representation: Disciplining and Domesticating Miss Moneypenny in Skyfall.” For His Eyes Only: The Women of James Bond. Ed. Lisa Funnell. London, UK: Wallflower Press, 2015. 70-78.

- Wagner, Travis L. “‘The Old Ways Are Best’: The Colonization of Women of Color in Bond Films.” For His Eyes Only: The Women of James Bond. Ed. Lisa Funnell. London, UK: Wallflower Press, 2015. 51-59.

Co-written with Klaus Dodds

In The World is Not Enough, Bond states that, “Construction isn’t exactly my specialty” to which M replies “Quite the opposite, in fact.” This exchange draws attention to the fact that Bond is a destructive hero who is not only armed with a “license to kill” but also with a “license to destroy.”

Bond makes claims on a range of spaces and his ruination of physical property plays a central role in shaping his heroic identity and professional prowess. While Bond sets out to destroy the villain’s expansive lair (usually in an explosive fashion), he rarely damages cultural artifacts and national monuments. In that sense the demolition and explosive work he engages in appear measured and proportionate. Importantly, Bond is rarely shown causing harm to animals/wildlife and takes care to rescue any person who is associated with him. His explosive capacity is thus targeted and when is he not able to destroy the villain’s lair he takes out specific elements of the villain’s portfolio.

However, as the series progresses, Bond becomes increasingly destructive and his license to destroy is amplified as the films become more action oriented. The Craig era origin trilogy amplifies the damage by setting a number of action sequences in construction zones—spaces that are partially built or destroyed, depending on how you look at it.

In Casino Royale, Bond engages in a parkour-inspired chase sequence through the construction zone of a high rise building in Madagascar. While Mollaka navigates his way over and around various obstacles, Bond rams through and destroys them in the process. This scene emphasizes Bond’s positioning in the Craig era films as a ‘blunt instrument’ whose approach to fieldwork is physical and forceful rather than subtle and nuanced.

Moreover, the construction zone can be read as a metaphor for the character of Bond. Monika Gehlawat argues that the placement of Bond in construction zones “accentuates his own attempts to emerge from underdevelopment” (2009, p.133). Over the course of three films—Casino Royale, Quantum of Solace, and Skyfall—Bond learns how to be a superspy and experiences growing pains as he learns from his physical, emotional, and psychological mistakes. The aforementioned sequence is part of Bond’s first mission after attaining his license to kill. While his desire to capture Mollaka is evident, he lacks the skill set to capture him quickly and efficiently. As a consequence, he ends up killing Mollaka and violating diplomatic protocols leading to his escapades being widely publicized in the media.

As a hero, Bond is a work in progress and this is symbolized through the use of construction sites to bookend Casino Royale. The final action sequence takes place in a partially renovated building in Venice. In her detailed analysis of the “aesthetics of demolition” in Casino Royale, Gehlawat draws attention to the movement and instability of the structure itself:

Stairwells and landings crumble and drop into the floors below and, eventually, into the canal. Light fixtures, balustrades and random objects (as well as people) seem to detach from the context and slide helplessly downward […] All the while the atmosphere of the scene is dark, confused and foreboding. The scene’s liminal quality manifests not only because it occurs in a space that is neither building nor rubble, but also because of the watery world that soon consumes it. (2009, p.137)

Gehlawat argues that this scene, in combination with the aforementioned chase in Madagascar, can be read as metaphors for the broader changes taking place in the Craig era as Bond is refashioned and updated (2009, p.137).

This scene can also be read diegetically. After discovering that his lover, Vesper Lynd, has betrayed him, he tracks her down to the building and fights her captors. Although this space is relatively empty, the construction equipment presents a new danger as it is mobilized as weapons for attack rather than pursuit. Unlike Moonraker, the conflict destroys the structure of the building, which collapses into the water below. Lynd eventually drowns after she locks herself in the elevator and refuses to be rescued. This scene can also be read as a metaphor for Bond as his faith in Lynd has been shaken and his world, much like the building, has come crashing down.

This foundational instability continues into the next film, Quantum of Solace, which opens with Bond transporting Mr. White to be interrogated by M in Siena, Italy. During the examination, M’s bodyguard Mitchell, who is working as a double agent for the Quantum organization, frees Mr. White. Bond’s pursuit of Mitchell leads them to a bell tower that is under renovation. The men crash through the glass on the roof and fall onto the scaffolding where they begin to use building materials as weapons. When Bond gets caught up in a rope, he swings upside down and struggles to reach his gun in time to kill Mitchell. Not only does the construction site increase the tension of the scene (as the viewer questions if Bond has what it takes to get the job done), but it also reflects the instability of M16 as an organization, which has traitors in its midst—first Lynd and now Mitchell.

Skyfall also uses construction zones and equipment to signify the end of the Bond’s origin story. In the pre-credit sequence, Bond uses a backhoe loader to deflect bullets on the train (although he does get shot) and create an opening to enter the train car; Bond can be seen jumping from the boom of the backhoe onto the carriage just as the back of the car is being peeled away. His progress is short lived (pun intended) as he is accidentally shot by Moneypenny and falls into the river below. This sets in motion a resurrection narrative in which Bond rebuilds himself physically, emotionally, and psychologically over the course of the film.

Bond comes across another construction zone while pursuing Silva who has escaped from M16 custody. It is here that Bond discovers Silva’s plan but not before the villain blows up a wall and causes an underground train derailment. Although Bond is a few steps behind Silva, he races through the streets of London as M recites a poem by Tennyson: “We are not now that strength which in old days moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are. One equal temper of heroic hearts, made weak by time and fate, but strong in will. To survive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.”

This sequence creates a visual and narrative contrast between Silva, a former M16 agent who deconstructs the system from the inside, with Bond, a hero who shores up the agency from the outside. And in the end, Silva cannot destroy the will of Bond or the ideals of M16 despite destroying part of the MI6 building. In the final scene of the film, Bond enters into the office of M, retrofitted to match the design of the early Bond films. Both Bond and M16 have been rebuilt as the last line of defense for Britain.

For a detailed discussion of Bond’s “license to destroy”, see our book Geographies, Genders, and Geopolitics of James Bond.

Co-written with Klaus Dodds

Bond is a global traveler and sent on missions throughout the world. Airplanes offer the most expedient form of transportation to and from these places. Bond can be seen boarding planes (The Living Daylights), traveling in flight (Goldfinger, 1964), and exiting airports (Dr No, 1962). Bond has fought henchpeople on the runway (Casino Royale, 2006) and in the air (Spectre, 2016), and has been debriefed by allies on the tarmac (Tomorrow Never Dies, 1997). He demonstrates his knowledge of aviation technology by flying various aircrafts (You Only Live Twice, 1967) and has brought wayward planes under control (Die Another Day, 2002).

While airplanes are featured in Bond films, they are not neutral technologies and are bound by social identities – particularly nationality for large airliners and gender for light and small aircrafts.

The airplane serves as a consistent reminder of the Anglo-American special relationship. When Bond flies commercially in the 1960s, his airline of choice is Pan American (or Pan Am). Bond is shown arriving in Kingston (in Dr No) and Istanbul (in From Russia with Love, 1963) courtesy of Pan Am. He is shown travelling again with them in Live and Let Die (1973) on a brand new Boeing 747 and aborts his travel plans with the airline in Licence to Kill (1989).

While Pan Am is associated with the travel plans of Bond early in the franchise, light and small aircrafts (but not helicopters as they were always flown by men with the exception of Naomi in The Spy Who Loved Me, 1977) are feminized and largely associated with female pilots. This is established in Goldfinger with the introduction of Pussy Galore and broadened in You Only Live Twice when the flying technology is explicitly feminized.

Little Nellie is the codename for the gyroplane developed by Q. Bond frequently refers to aircraft using feminine pronouns and even refers to it as “girl”. Little Nellie’s youthfulness – due to her size and newness as a technology – is being signalled through her familial relationship as a daughter with a father/creator, Q.

Language also helps to draw parallels between the gyroplane and the Bond Girl as Bond refers to both as “good girls.” This is notable through his radio transmission following his success in an aerial fight: “Little Nellie got a hot reception. Four big shots made improper advances toward her, but she defended her honour with great success. Heading home.”

The term “girl” has historically been used as a way to diminish, deprecate, and trivialize (grown, professional) women by labelling them as immature or inexperienced. As a result, the depiction of Little Nellie not only aligns her with the Bond Girl (i.e. grown women described as Bond’s girl – see previous blogs) but also emphasizes the patriarchal role that Bond plays via touch. His heroic identity is defined not only through his seduction and domestication of the Bond Girl but also through his mastery of/over feminized technology like Little Nellie.

In addition to the feminization of small and light aircrafts, flying is often presented as a female profession in the Connery era and Bond’s ability to seduce a female pilot is a key factor in the success of his mission. This is most evident in Goldfinger as the villain has hired Pussy Galore to be his personal pilot. She is also a flight instructor and the head of an all-female flying troupe comprised of five beautiful women dressed in black spandex uniforms that emphasize femininity and attractiveness. These women will participate in Goldfinger’s Operation Grand Slam by crop-dusting the military surrounding Fort Knox. Thus, Bond’s ability to seduce Galore (and by extension her troupe) away from the villain proves to be the tipping point in his mission. After their sexual encounter, she exchanges gas canisters and works with the CIA to foil Goldfinger’s plan.

Extrapolating from the character of Galore, You Only Live Twice establishes the figure of the personal assistant pilot. Helga Brandt is introduced as the secretary and pilot of Mr. Osato, a Japanese industrialist who is affiliated with SPECTRE. While Brandt is a SPECTRE agent and number 11 in their hierarchy, she works in a supportive role rather than management in the office. Although Blofeld orders Brandt to kill Bond, she is seduced by him and this delays her assassination attempt. The next day, she puts a plan into play that consists of strapping Bond into a small plane and parachuting out, leaving him to die in the crash. After Bond escapes, Brandt is punished for her failure by being dropped into a pool of piranhas where she is eaten alive. As instituted by the Connery era, the seduction of the personal assistant pilot is pivotal to the survival of Bond and the success of his missions, and usually occurs at her expense – professionally and/or personally.

In the Moore and Dalton eras, female pilots are presented as either a personal assistant to the villain and/or Bond Girl pilots who work with/for Bond. For instance, in Moonraker (1979) the scantily clad Corrine who works for Hugo Drax becomes an asset to Bond soon after she gives him a flying tour of the Drax personal estate and space shuttle testing institution. After Bond seduces her, he tricks her into revealing the location of her employer’s safe. After Bond leaves, she is killed by Drax who sends his Rottweilers to chase her down in the forest. Thus the personal assistant pilot is a highly sexualized and disposable object of desire that is killed off as soon as she loses usefulness to Bond and/or the villain.

In comparison, the Bond Girl pilot plays a pivotal role in the success of Bond’s mission. In Moonraker, Dr. Holly Goodhead is introduced as an astronaut and scientist working for Drax. Although Bond initially assumes that Goodhead, like Corrine, is a personal assistant pilot he can seduce, he soon discovers that she is an undercover CIA agent and changes his approach by suggesting that they work together platonically. While Goodhead flies them into space, Bond demonstrates his intuitive understanding of aeronautics and astronautics that allows him to use the technology. And it is only after the mission has been completed that Bond finally seduces Goodhead and their zero-gravity lovemaking session is accidentally transmitted to the base back home.

In License to Kill, Pam Bouvier is presented in a similar way as she is a pilot and CIA agent who assists Bond on his mission. She flies Bond to Isthmus City for the undercover mission and Bond introduces her as his personal assistant, a cover identity that does not go over well with her as she would rather be his boss. Bond tells her that she needs to look the part and Bouvier undergoes a makeover to increase her sex appeal; she returns with a slick haircut and formitting dresses that support her cover as a personal assistant pilot. Although Bouvier offers tactical support in the air, she operates on the periphery of the final action sequence as she flies in a crop-dusting aircraft and remains out of the conflict while Bond performs the majority of the heroic labor by confronting Sanchez in a tanker-truck chase. And like Goodhead, she consummates her relationship with Bond once the mission is complete when he chooses her over his Latin lover, Lupe Lamora.

In the Brosnan era, the female pilot is reimagined as a central antagonist through the figure of Xenia Onatopp in GoldenEye. Onatopp is initially presented as being a personal assistant pilot to General Ourmunov for whom she steals the Tiger helicopter in order to transport him to Siberia. This role is suggested through costuming, as she wears revealing clothes such as a low cut dress and a bathrobe, as well as Bond’s interest in seducing her at the casino, albeit with no success. It is later revealed that Onatopp is actually working for Alec Trevelyan and no longer functioning as a potential conquest or tipping point for Bond. This is signalled through a change in costuming as she wears a black military-styled uniform when she abseils from a helicopter to attack Bond. She is subsequently killed when Bond shoots at the aircraft, which leads to her suffocation against a tree. As the last female pilot appearing in the franchise, Onatopp highlights the dangerous role that female pilots play when they cannot be seduced or domesticated by Bond.

The intersection of nationality and gender draws attention to the geopolitical significance of the gendering of light and small aircrafts and the representation of female pilots. Importantly, only American women serve as Bond Girl pilots (Galore, Goodhead, Bouvier) while women who lack obvious national affiliation take on the secondary role of personal assistant pilot (Brandt, Naomi, Corrine). This highlights the central role that the United States has historically played in aeronautics and astronautics, and Bond’s ability to fly helicopters, light planes, fighter jets, and military transport aircrafts helps to counter-balance that aerial/aeronautic dominance. In comparison, the only female antagonist pilot (Onatopp) was once affiliated with the former Soviet Union and the theft of this technology along with Bond’s inability to seduce her, renders her as a genuine threat.

Through its representation of female pilots, the Bond franchise appears to reiterate an antiquated message that was once relayed to American and Soviet female pilots after World War II about the reestablishment of gender roles – they were expected to return to their prewar (domesticated) roles in society. Through his seduction of female pilots, Bond orients them away from the cockpit and toward the domestic sphere with his loving touch.

For a more detailed discussion of planes, trains, and automobiles in James Bond, see my book with Klaus Dodds on Geographies, Genders and Geopolitics of James Bond (2017).

The “Bond Girl” is a staple of the Bond series and has strongly contributed to the global appeal of the franchise. In popular discourse, the term “Bond Girl” has been overused and frequently applied to virtually every woman who has appeared in a Bond film regardless of their role or centrality to the narrative. There is a difference between a primary character and a secondary figure who may or may not (be important enough to) be named. Additionally, female protagonists are conceptualized, cast, and treated differently in their narratives than their villainous counterparts (see my blog series on “Feminism and Female Villainy” for details). The overuse of the term “Bond Girl” is one reason why women in the Bond franchise have been overlooked (particularly in academic scholarship at least in the fields within which I work) and quickly written off as window-dressings and sexy pin-ups.

In his novels, Ian Fleming used the term “girl” to refer to the female love interest of Bond. His moniker has been expanded into the term “Bond Girl” which is now widely used in social and academic circles. However, there are many people who find the term problematic or at the very least feel uncomfortable using it, including myself.

First, the use of the word “girl” to refer to professional women works to infantilize them, diminish their accomplishments, and reduce their importance in the film. (A similar argument can be made about the use of double entendres for names. Can we take a pilot named Pussy Galore or a scientist Dr. Holly Goodhead seriously? These names ensure that we do not and detract from their abilities and accomplishments in their films). The term “girl” also works to emphasize their single status with “woman” being reserved in the series for marriage and maternity. Much like the term “boy” can be used to insult a man – as demonstrated by Sheriff Pepper in Live and Let Die (1973) – the same is true for the term “girl” when it is used to describe adult professional women. Importantly, men in the series are not referred to as “boys.” Allies like Felix Leiter, villains like Blofeld, and henchpeople like Jaws are not described as being “Bond Boys.” So why then do we refer to adult women as “girls”?

In addition, the inclusion of the word “Bond” before “Girl” tells us that the woman is being (solely) defined by her relationship with Bond. She does not have an individual or standalone identity. It also suggests a level of possession – that she is Bond’s girl – and will be positioned as an object (not subject) of struggle between Bond and his male adversary.

There are many people – fans, critics, and scholars – who are uncomfortable with the term Bond Girl. In addition, some women who have been featured in the Bond series have also expressed their distaste for the term, Monica Bellucci being the most notable. Rumor has it that the term was banned from the set of the upcoming Bond film No Times To Die with the instruction that female actors should be referred to as “Bond women” instead. While it is difficult to avoid using the term “Bond Girl” due to its cultural pervasiveness – it has been around for nearly 60 years and has become ingrained in social and academic discourse – we need to be mindful of the messages being conveyed through the term about gender, sexuality, identity, and power.

In this blog, I will use the term to refer to the archetype but also employ other descriptors like female protagonist and Bond women in order to reduce its frequency of use.

The Archetype

It is important that we define and clarify the term Bond Girl in order to untangle the web of women who appear across the franchise and better understand the form and function of the lead protagonist in a Bond film. The term refers to a character archetype. She is not a recurring character (i.e. she only appears in one film) but a recurring character type. Each Bond film features a different female protagonist who is played by a different actor. While Bond interacts sexually with various women in each film, he commits himself to the lead heroine by the end of the narrative. They engage in a monogamous and committed relationship (that has ended by the start of the next Bond film). Given this definition, there can only be one “true” Bond Girl in each film.

The Bond Girl is also a “good” character who assists Bond in some way with his mission. Some women play more central and direct roles than others. While some offer physical help, others provide intellectual assistance, and/or emotional support/motivation. The degree of heroism ranges and seems to depend on when the film was made as well as the star persona and performance abilities of the actor playing the role.

There haven been three character phases for the Bond Girl:

* English Partner (1962-69)

* American Sidekick (1971-89)

* Action Hero (1995-2002)

I will discuss the deconstruction and reintroduction of the Bond Girl archetype across the Craig era films in my next blog.

English Partner (1962-69)

The first character phase of the Bond Girl is the English Partner. The Bond films of the 1960s mirror the male-female partnership featured in The Avengers (1961-69), a popular British spy television series centered on a male-female heroic duo. The character John Steed was partnered with a female hero and two of these women were subsequently featured in Bond films: Honor Blackman played Dr. Cathy Gale (1962-64) and Diana Rigg played Emma Peel (1965-67).

The English Partner was often anglicized. On the one hand, Blackman who played Pussy Galore in Goldfinger (1964) and Rigg who played Tracy DiVicenzo/Bond in OHMSS (1969) used their own voices and natural English accents. On the other hand, the voices of other female protagonists in the 1960s – Honey Ryder in Dr No (1962), Domino Derval in Thunderball (1965) and Kissy Suzuki in You Only Live Twice (1967) – were dubbed in post-production by Monica van der Zyl. The only exception is Tatiana Romanova in From Russia with Love (1963) whose voice was dubbed by Barbara Jefford. Thus, the female protagonists frequently spoke with an English accent (hence the label “English Partner”) and many of them spoke with the very same voice regardless of the nationality of the actor or the character. This is one reason why my students find it difficult to determine the nationality of female protagonists in the Connery and Lazenby eras based on voice/accent alone!

As noted in my first blog post on “Feminism and Female Villainy,” the imaging conventions for 1960s Bond Girls reflects Ian Fleming’s character design of the “girl” in his Bond novels. These women have blonde, brown or black hair, with red hair being reserved for the villains: in the novels it was used in the description of male villains but in the films it was reserved for the female ones.

Things began to change with the final English Partner, Tracy DiVicenzo in OHMSS (1969), and the first American Sidekick (see description below), Tiffany Case in Diamonds Are Forever (1971). They both have red hair. This change anticipates/highlights a broader shift in the representation of the figure. Often in film, a change in image signals a shift in characterization. In other words, internal changes are depicted externally and often through visual conventions like costuming and hair. (The film Thelma and Louise [1991] offers a good example of this).

In fact, Diamonds Are Forever explicitly plays with this imaging/hair convention during the introduction of Tiffany Case. She first appears as a blonde, then a brunette, and finally emerges with her natural red hair and remains this way for the remainder of the film. This play on hair color offers a way to visually connect the women of the past (i.e. the English Partners of 1960s) from those of the future (i.e. the American Sidekicks of the 1970s).

American Sidekick (1971-89)

The second character phase for the figure is American Sidekick. Over a two-decade period from 1971 to 1989, many female protagonists were American agents or allies as well as the actors who portrayed them. The American Sidekick embodies American interests in the film and she even replaces Felix Leiter as Bond’s American connection. In fact, when a female CIA appears in a Bond film, Leiter is absent. The only exception is Licence to Kill (1989) in which Pam Bouvier replaces Leiter as Bond’s American sidekick after he is attacked by Frank Sanchez.

In the case of the American Sidekick, the Bond films re-frame the British and American geopolitical relationship via romance. This changes the dynamic by tapping into traditional gender roles. Bond seems inclined to one-up his American Sidekick in order to demonstrate that he is the superior agent. This in turn influences the perception of British and American relations in the films. For a detailed discussion, see my article with Klaus Dodds on “The Anglo-American Connection: Examining the Connection of Nationality with Class, Gender and Race in the James Bond Films.”

Overall, in the first three decades of the franchise, Bond Girls play more supportive roles in their films. It is not an equal weighted partnership and Bond still does the majority of the heroic labor in the film. She is not presented as being a co-hero or heroic equal, and at times she does not even engage in the space of physical action. Instead, English Partners and American Sidekicks serve more as love interests and mediators of threat. In other words, a threat to them propels Bond into action. At the end of the day, it is Bond (oftentimes alone) who is the hero and saves the day.

Action Hero Bond Girl (1995-2002)

The third phase for the Bond Girl is the Action Hero. She appears in the Brosnan era films which are more action oriented than their predecessors and reflect the rise of blockbuster action filmmaking (as well as female action heroism) in Hollywood. In the Brosnan era, Bond is presented more as of a man of action than a lover and the role of the Bond Girl seems to adjusted in a similar way.

As an Action Hero, the female protagonist plays a central role in the narrative and is (far) more active and engaged in the space of physical action. She is largely presented as being a co-hero to James Bond. Pam Bouvier in the final Timothy Dalton film Licence to Kill (1989) is a good precursor to this shift as she is more action inclined and takes part in the heroic labor. Women in the Bronsnan era seem to more forward from there.

The Action Hero is presented as more of an equal to Bond. She may question or challenge his authority, disagree with his plan and suggest a new one, or even take the lead and Bond follows her. She takes more initiative and works with rather than for Bond. Natalya Simonova clearly establishes this dynamic in GoldenEye (1995).

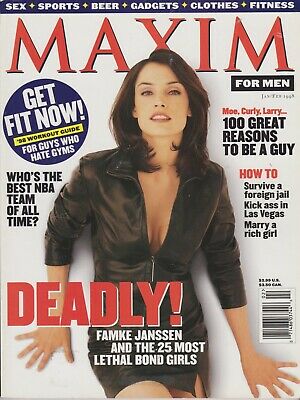

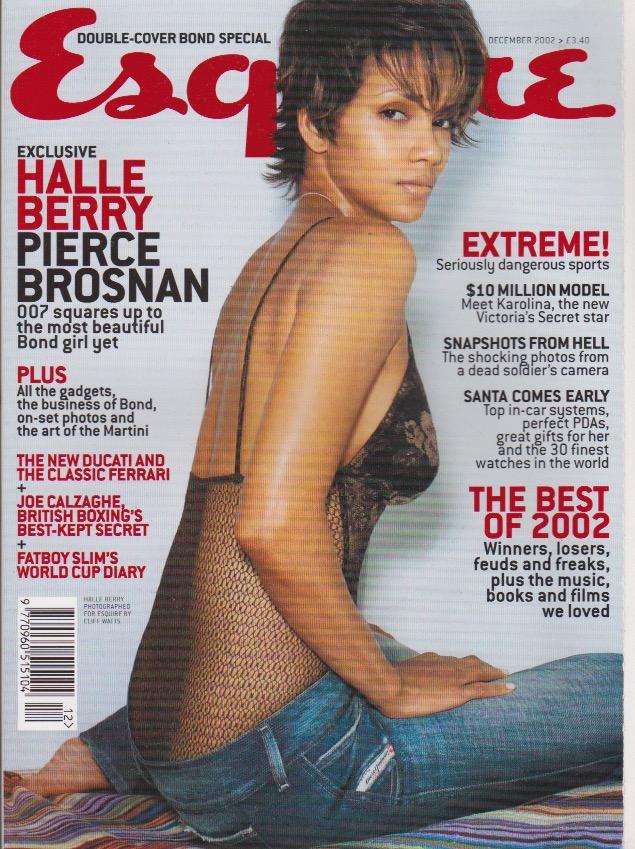

The shift towards more action-oriented women is notable through casting. Two actors featured as Bond Girls had great star power with notable action film credentials. Michelle Yeoh was a bonafide action superstar across East and Southeast Asia prior to her casting in Tomorrow Never Dies (1997). Halle Berry had also starred (and has conintued to be featured) in Hollywood action films prior to her casting in Die Another Day (2002). Overall, these Bond women are far more action-oriented than their predecessors.

For example, Michelle Yeoh performed her own stunts in Tomorrow Never Dies. She even brought her own action choreographer and stunt team from Hong Kong. She is the first woman to be featured in her own action sequence and she is even equipped with her own Q-like spy gadgets. It is Bond and not his female co-star who is the butt of the film’s jokes.

The Gaze (Laura Mulvey)

Bond Girls have long been defined by “the gaze.” In the 1970s, scholar Laura Mulvey published her “gaze theory,” sparking the development of feminist film theory and drawing attention to the gendering of media images. Although her theory is detailed and multifaceted, the following is the crux of it.

According to Mulvey, the gaze in film is male. The lead male character is an active gazer in the film. He is the subject who possesses the gaze and the one who does the looking. In comparison, the female is an object that is being looked at. She is passive, and her body is placed on display and gazed upon. Through camera work, the spectator shares the point-of-view (POV) of the male gazer and looks at the women featured in the film. Mulvey draws attention to the gender binary at the heart of media images: the active male subject vs. the passive female object.

Mulvey further argues that women possess “to-be-looked-at-ness.” Women are presented as erotic spectacles and pin-ups in their films. They play to and signify male desire (in a heteronormative context). In addition, her visual presence in the film tends to work against story development. She freezes the flow of action and creates moments of erotic contemplation. The male hero often stops to gaze at her.

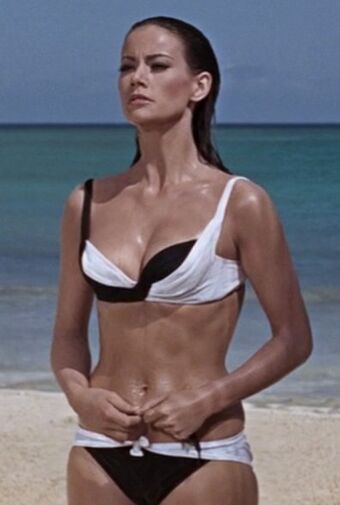

From the outset of the franchise, the Bond Girl has been positioned as the object of the gaze. She is presented as a visual spectacle in her films. She is set up for Bond to gaze upon and the audience, who share Bond’s perspective, are also encouraged to look at her. Moreover, the female protagonist frequently appears in lingerie and bathing suits. These work to enhance her sex characteristics as they highlight her breasts, stomach, hips, and legs.

In the first Bond film, Dr. No (1962), the inaugural Bond Girl Honey Ryder is introduced as an object of the gaze. Bond wakes up on the beach of an island to the sound of a woman singing. He looks out into the water and spies Ryder emerging from the sea in a white bikini. During their first meeting, Ryder asks if Bond is looking for shells and he responds with “no, I’m just looking.” The camera shares Bond’s POV and the viewer is encouraged to look at her too (hence, “the gaze”). Moments later when Quarrel runs towards Bond, he stops in his tracks and stares of Ryder. He loses his capacity to speak and his mouth hangs open. This arresting image of Ryder in a bikini literally freezes the flow of action.

Die Another Day (2002) features an homage to this iconic scene in its introduction of Jinx Johnson. Bond gazes at her through binoculars while standing on the shore. He watches as she emerges from the water in an orange bikini and walks towards him. During their first meeting, he says “magnificent view” commenting on her physique (rather than the scenery behind her). Even though Johnson is an Action Hero who is presented as an equal and co-hero to Bond, she is still introduced and defined through his male gaze.

This leads to an important line questioning: Does this mode of representation enhance or detract the Bond Girl’s heroism? Does it work to trivialize or diminish her character? Or is this simply a fundamental element of the archetype that she can’t move past?

Freedom or Exploitation?

The Bond franchise has been criticized for being many things (such as racist, heterosexist, classist, xenophobic) including sexist and misogynistic. Misogyny refers to the dislike of, contempt for, and ingrained prejudice against women. Misogyny can manifest in many ways such as sexual discrimination, objectification, and violence directed towards women. Although Bond films are rooted in the sexual politics of the 1960s, a seemingly more liberal/liberated era, some have questioned if women in the Bond films are truly free or if they are simply being exploited under the guise of freedom. As Arthur Marwick has stated: “Was this sexual liberation for women, or simply enhanced liberation for men, a grand occasion for even the more ruthless sexual exploitation of women?”

Most Bond films feature at least one women semi-nude and in various stages of undress. This is in addition to the many anonymous/unknown women who are featured in the opening credit sequence. Emphasis is placed on female bodies, which are partially if not fully nude and presented in shadow or silhouette. The objectification of women has long been a marketing feature of the franchise. It is also a core element in promotional materials such as movie posters and men’s magazines.

There is an interesting relationship between the Bond franchise and men’s magazines. Claire Hines has done great work on this topic as well as Stephanie Jones!

Playboy is an American men’s lifestyle magazine that features nude photographs of women as well as journalism and fiction. It has a long history of publishing short stories by notable novelists including Ian Fleming with “The Hildebrand Rarity” in 1960 as well as “Octopussy” posthumously in 1966. In addition, many women featured in the Bond films have posed for Playboy. Their photo-shoots coincide with the release of their films and some even took place on set after the films were shot. There is a long tradition of Bond women appearing in Playboy especially in the first three decades of the franchise.

Various issues of Playboy correspond with the release of a Bond film. The women featured in them are photographed nude and semi-nude, and their poses and settings recall their roles in their respective Bond films. All women from major to minor figures are marketed as “Bond Girls” regardless of their role or function in the films. These photos also help to reaffirm the male gaze. They emphasize the pleasures of looking at the women of Bond. The reader can see more of Bond’s co-stars than shown in the films. In essence, the reader is offered a glimpse of what Bond gets to see behind closed doors since the film proper does not contain any nudity (beyond the opening credit sequences).

Since the 1960s, Playboy has (un)covered many of the Bond films with pictorials:

In addition to Playboy, the women of Bond are also featured in other men’s magazines that range from “adult” or pornographic content to more mainstream images. They have been featured in Maxim, Arena and FHM to name a few. Even though these women are wearing more clothing, this remains a problematic and reductive mode of marketing. These women seem to be defined by their beauty/bodies rather than by their performance or skills. Since the 1990s, there has been a lot of talk about how gender politics have progressed in the Bond franchise and the world beyond, but compared to the 1960s are the women of Bond valued more, less, or the same?

In the mid-1990s, the Bond franchise returned after a 6-year hiatus. During this time, the series renegotiated some of its codes and the Brosnan films have been updated in terms of gender politics. Now, the Bond films did not necessarily alter Bond’s attitude towards women. Instead, they adjusted the attitudes of women around Bond. They forward the impression that the while the world has changed as well as the women who inhabit it, Bond has remained the somewhat the same and will face some new challenges (in the workplace/field).

Postfeminism

Bond films of the 1990s (like many other spy narratives) are strongly influenced by postfeminism. This is a popular social movement among some (privileged) women that is centered on the belief that feminism has won its battles. It promotes the idea that (the need for) feminism is over and women have achieved social equality. As suggested by the prefix “post” (which means “after”), this movement claims that we are living in the time after feminism.

(It is important to note that third wave feminism and postfeminism take place at the same time. They relay different impressions about the social status of women and the need to fight for equality.)

One key idea forwarded during postfeminism is that femininity has been demystified. In other words, women are no longer being held back their gender. As a result, they can (re)claim their sexuality and use it personal gain without being judged harshly by others/society. “Girl Power” (popularized by the Spice Girls) was a notable expression of postfeminism at the time.

Many scholars have strongly criticized the postfeminist movement and believe that it relays some troublesome messages. First, postfeminism is an exclusive movement that focuses on the experiences of certain women: white, middle-class, able-bodied, heterosexual, Western, Northern, and cis-gender. It takes their experiences as the universal experience for all women (much like the second wave concept of “universal womanhood”). As a result, it overlooks the lives, intersectional identities, and experiences of all women. Second, postfeminism is very narrow and overlooks the multitude of ways that women are marginalized based on their other social locations: race, class, ability, sexual orientation, nationality, and gender expression.

Third, postfeminism overlooks the fact that gender oppression still exists. The gender pay gap is a good example of this. There are many other social and structural limitations for women in addition to people who are trans, non-binary, queer, or identify in other ways. Finally, postfeminism discourages women from taking action to change their social circumstances and encourages them to be happy with the status quo. This raises an important question as to who benefits from postfeminist ideas and their transmission via film, television, and music (among other medias) in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Sexually Empowered Villains in the Brosnan Era

Postfeminism strongly informs the depiction of female villains in the Brosnan era and Bond is challenged by them in 3 out of 4 films. These women rely on duplicity to gain power over Bond and play on his affinity for sexual conquest and domestication. Importantly, they use their sexuality for personal gain and sleep with Bond in order to develop an emotional connection with him. Some even masquerade as Bond Girls in need of protection (and could be considered Bond Girl-Villain hybrids). Ultimately, the goal here is to use Bond’s libidinal masculinity against him and render him (more) vulnerable for attack. A good example is Miranda Frost in Die Another Day (2002) who literally disarms Bond’s gun (with phallic connotations) while they are in bed together.

In the Brosnan era, the gender politics governing Bond’s “licence to kill” have also been updated. Bond kills his adversaries regardless of their gender. In other words, he can and does kill women. He is able to (re)assert his masculinity over dangerous women with liberal sexual identities who challenge his phallus. Moreover, his method of killing them is often ironic and reflects their sexual threat to him in the film. Xenia Onatopp from GoldenEye (1995) is the best example of this. Onatopp is a sadist who takes sexual pleasure in inflicting pain on others. During coitus, she wraps her legs around her (usually male) target and squeezes until they asphyxiate. She is eventually killed by Bond who attaches a harness from a helicopter to her belt and she is asphyxiated between two tree branches that look like a pair of legs. Onatopp is killed in the same way that she killed men and threatened Bond.

Of all the female villains in the Brosnan era, Elektra King featured in The World Is Not Enough (1999) warrants special attention. King masquerades as a Bond Girl and damsel in distress only to emerge as the primary/arch-villain in the end. She is the first woman to serve in this capacity and much like other core villains she has her own musical theme. What makes her a memorable villain is the way that she plays on the emotions of Bond and Judi Dench’s M, albeit in different ways; her seduction of Bond (and later sexual torture) challenges the effectiveness of his libidinal masculinity while her emotional manipulation of M plays on her maternal instincts. King is underestimated as a threat and this is reflected in the Elektra Theme, which is slow and melancholic, framing her as a tragic and (somewhat) helpless figure while masking her true intent from Bond, M, and MI6 as well as the viewers. We are all seduced by her.

While some might argue that Renard is the primary villain, he serves as more of a traditional henchperson with a biologically altered/enhanced body (think: Oddjob in Goldfinger [1964], Tee Hee in Live and Let Die [1973], and Jaws in The Spy Who Loved Me [1977] and Moonraker [1979]). Moreover, his pairing with King is reminiscent of Zorin and May Day in A View to a Kill (1985) with the henchperson being more emotionally/romantically invested in the relationship than the primary villain. While Renard lacks the ability to feel physical pain, King is depicted as a sociopath who lacks the ability to connect emotionally. This makes their pairing interesting (i.e. they have what the other lacks) but also unsustainable (i.e. they will never be fulfilled). Much like May Day, Renard comes across as more of a tragic figure given his unrequited love for the villain that cannot be returned.

The Case of Valenka

Casino Royale (2006) ushered in a new era of James Bond. The film is a prequel and presents the origin story of the title character from the moment he attains his “00” licence to kill. The Craig films deconstruct the Bond brand and gradually reintroduce core elements across the era. While a comprehensive discussion of the Craig era is beyond the scope of this blog (and possibly a future posting topic), it important to note that the heroic model governing the series has changed.

As I have argued elsewhere, there is a shift in Casino Royale away from the “lover literary tradition” from which Bond has his roots and towards a more Hollywood-styled hard-bodied mode of masculinity. In other words, Bond is defined less by sexual conquest and more by the way in which he endures and overcomes physical pain. Craig’s Bond is the most battered, bruised, and bloodied in history, and his action sequences are more visceral, graphic, and (hyper)violent. As the model of heroic masculinity governing the series changes, so too are the ways in which Bond’s heroism are tested and confirmed. With respect to female villainy, this requires a shift from sexual to physical threats.

Valenka featured in Casino Royale is the only notable female villain across the Craig era. She is introduced as the girlfriend and employee of the primary villain Le Chiffre. She has little dialogue and limited personal agency in the film. Instead, she is paraded around in revealing garments like bathing suits and gowns in order to offer a visual distraction to Le Chiffre’s poker opponents.

Unlike other female villains, Valenka does not interact with Bond sexually. She does not seduce Bond and Bond does not seduce her. In fact, there is no sexual tension or interaction between the characters. Instead, Valenka remains in a seemingly monogamous relationship with Le Chiffre. Since the heroism of Bond has changed from libidinal to muscular/body-based, so too are the ways in which his heroism is challenged by villainous women.

In spite of her characterization or maybe even because of it, Valenka is underestimated as a threat to Bond. However, she is one of Bond’s most dangerous adversaries because she succeeds where others have failed. She is the only villain to actually kill James Bond, even though he is resurrected shortly after. This renders Valenka one of Bond’s most dangerous opponents.

Although Valenka is a threat to Bond, she is disempowered over the course of the film. She is set up as a dependent rather than independent/autonomous character. Unlike female villains of the 1960s who make their own decisions while working for Blofeld, Valenka lacks an individual identity and sense of purpose. She is presented as being a function of Le Chiffre and not his partner/equal. While we clearly know what motivates him, we get no insight into what is driving her (maybe love?). Her silence is quite deafening in this respect.

We also get the sense that Le Chiffre might not care for her all that much. When Le Chiffre and Valenka are attacked in their hotel room, Le Chiffre does not call out or try to stop the assailant from hurting Valenka. The attacker even notes Le Chiffre’s lack of protest; he was willing to sacrifice Valenka in order to save himself. This is different from Bond’s attempt at saving Vesper Lynd in the stairwell in the next scene. This works to further contrast Bond and Le Chiffre in the film particularly with respect to their romantic relationships.

The fate of Valenka is also quite telling. While we see LeChiffre die through Bond’s point-of-view – he is killed in the climax of the film and his lifeless body falls to the ground – Valenka’s death occurs off screen. It is only mentioned in passing during a conversation between Bond and M. Given the mortal threat she posed to Bond, it is surprising that she is not killed on screen. Instead, her death is presented as a by-product of Le Chiffre’s failed business with Mr. White rather than punishment for her mortal attack on Bond. This goes to show just how disempowered she is when compared to the female villains of the past.

Late Craig Era

Since Casino Royale, there has yet to be another substantial female villain in the Craig era films. While some might argue that Severine from Skyfall (2012) is a central figure/antagonist, I see her as more of a secondary figure with limited purpose. Unlike other kept women like Domino Derval in Thunderball (1965) and Andrea Anders in Man with the Golden Gun (1974), Severine could easily be removed from the film with little disruption to the plot line. Moreover, she is one of the most disempowered and tragic women featured in the series. For a detailed discussion of Severine and the racial stereotypes framing her representation, see my article “(D)Evolving Representations of Asian Women in Bond Films”.

With the release of No Time To Die, it will be interesting to see if either Nomi or Madeleine Swann will take up this role. Trailers for the film suggest both are possibilities but we will need to wait until November to see.

May Day! Disappearing Women!

Bond films of the 1970s present different politics of representation. They feature narratives in which women are being ‘put back into their place’ within the (hetero)patriarchy as the franchise registers the feminist backlash and resistance to feminist gains of the 1960s. They reflect concerns over the changing social status of women. As noted by Tony Bennett and Janet Woollacott: “This shift in narrative organization clearly constituted a response – in truth, somewhat nervous and uncertain – to the Women’s Liberation movement, fictitiously rolling-back the advances of feminism to restore an imaginarily more secure phallocentric conception of gender relations” (28). Phallocentric refers to the focus on the phallus/penis as a symbol of male dominance. Bond films of the 1970s emphasize Bond’s libidinal masculinity while downplaying any challenges to it.

As a result, female villains in the 1970s play relatively minor roles in their films. They were presented as incompetent spies like Rosie Carver in Live and Let Die (1973), tragic mistresses like Andrea Anders in Man with the Golden Gun (1974), and sexy secretaries like Naomi in The Spy Who Loved Me (1977). The agency, competency, and autonomy that defined female villains (like Rosa Klebb and Fiona Volpe) of the 1960s have been reduced and diluted in the 1970s. By the 1980s, few villainous women appear in the franchise at all. Over a 2-decade period the Bond franchise phased out images of “bad” women in order to focus on the domestication of “good” women (i.e. the Bond Girl) and emphasize the success of Bond’s phallic masculinity.

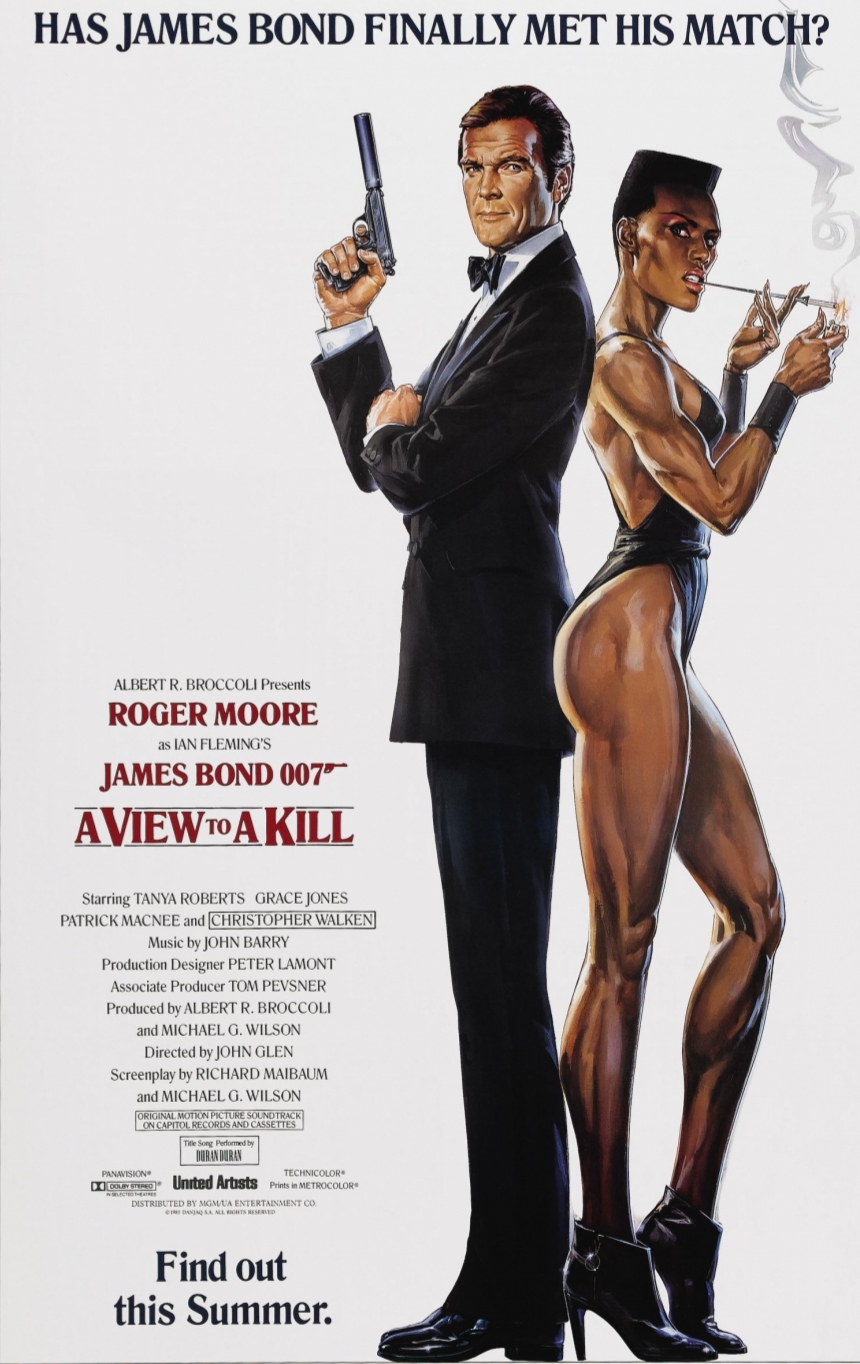

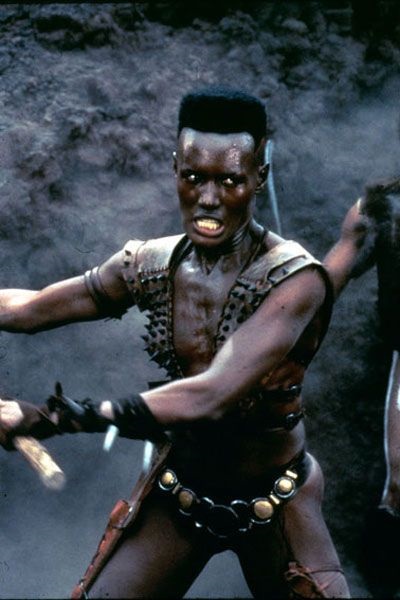

Has James Bond Finally Met His Match?

The only substantial female villain of the 1980s is May Day played by Grace Jones in A View to a Kill (1985). Even though May Day is not the arch-villain, she is privileged in the promotional materials for the film. One notable poster features an image of Bond and May Day standing back to back with the tagline “Has James Bond finally met his match?” While Bond is wearing his trademark black suit and holding a gun, May Day is dressed in a black one-piece bodysuit and heels while smoking. The image emphasizes her toned and muscular body while objectifying and sexualizing her in the process. As a result, her strength (via muscularity) and sexuality (given the phallic nature of her elongated cigarette) are presented, from the outset, as threatening to Bond.